Introduction: Seeing the Unseen World of Granulation

Imagine inside a rotating drum, thousands of fertilizer particles are undergoing complex collisions, mixing, and agglomeration. This process determines the final size, shape, and strength of fertilizer granules, directly impacting fertilizer quality and application effectiveness. However, this dynamic process occurs inside enclosed equipment, invisible to the naked eye. Traditional experimental methods can only see the final result, making it difficult to understand what happens in between. The Discrete Element Method (DEM) acts like a “digital microscope,” capable of precisely simulating the motion trajectory and collision process of each particle, allowing researchers to “see” the microscopic world of granulation, thereby optimizing equipment design and process parameters.

I. What is the Discrete Element Method? A Digital Laboratory for Granulation Research

The Discrete Element Method is a numerical simulation method based on Newton’s second law of motion. It treats each particle inside the granulator as an independent individual, calculating the forces acting on each particle (gravity, friction, collision force, cohesive force, etc.), then determines the particle’s position and velocity at the next moment based on these forces. By tracking changes every microsecond for millions or even billions of particles, DEM can reconstruct the dynamic scenario of the entire granulation process.

For studying drum granulators, a DEM model needs to include three key components: first, the equipment model—accurately replicating the drum’s dimensions, inclination angle, and internal lifter structure; second, the particle model—defining physical properties like particle size, density, and friction coefficients for seed cores and coating powders; and finally, the bonding model—simulating how binders “glue” particles together to form agglomerates. This digital laboratory can repeatedly conduct “virtual experiments,” changing parameters like rotation speed, inclination angle, and feed rate to observe how these changes affect granulation outcomes, without consuming real materials and energy.

II. Revealing Three Motion States Inside the Drum

Through DEM simulation, researchers have discovered three distinct motion states of particles inside the drum, with drum rotation speed being the key determinant:

1. Sliding State (High Speed)

When the rotation speed is too high (typically over 20 rpm), centrifugal force causes particles to cling tightly to the drum’s inner wall, sliding as the drum rotates, like riding a roller coaster. In this state, there is almost no relative motion between particles; coating material cannot uniformly adhere to seed surfaces. It’s like a crowd squeezed in a rotating Ferris wheel, unable to interact with each other. Granulation effectiveness is poorest in this scenario.

2. Slumping State (Low Speed)

When the rotation speed is too low (typically below 10 rpm), particles cannot be lifted to a sufficient height and merely slide slowly down the drum’s inner wall, like sand in an hourglass. Collision frequency between particles is low, mixing is insufficient, and coating is uneven. This is like gently shaking a can of mixed nuts—large and small particles tend to separate.

3. Cataracting State (Medium Speed)

At moderate speeds (typically 10-20 rpm), lifters carry particles to a certain height before they cascade down like a waterfall. In this state, particles gain maximum mixing energy, collision frequency is moderate, and coating material can uniformly adhere to seed surfaces. This is the “golden zone” for granulation, and DEM simulation helps precisely identify this optimal speed range.

Besides rotation speed, the drum’s inclination angle also plays a significant role. The inclination angle determines the “travel” time of particles through the drum: a steeper angle means faster particle movement from feed to discharge, with shorter residence time; too shallow an angle causes particles to accumulate near the feed end. DEM can precisely calculate the residence time distribution of particles at different inclination angles, helping find the optimal balance between granulation effectiveness and production efficiency.

III. Binders: How Does the Invisible “Glue” Work?

Binders are the “invisible heroes” of the granulation process. In DEM models, the effect of binders is simulated through special “cohesive force models.” For liquid binders (like starch solutions), the “liquid bridge force model” is commonly used: when two particles are connected by a thin liquid film, the liquid’s surface tension creates a force pulling the particles together, much like how two wet glasses are difficult to separate.

DEM simulation reveals the subtle relationship between binder concentration and granulation effectiveness: concentration too low results in insufficient liquid bridge force, causing particles to disperse easily and preventing stable agglomerate formation; concentration too high causes excessively strong cohesive forces, making many particles stick together into large clumps, leading to a wide particle size distribution. Through simulation, the optimal binder concentration for specific materials can be found.

Interestingly, DEM also discovered that collision energy significantly impacts agglomerate strength: moderate collisions help compact the agglomerate, increasing granule strength; but excessive collision energy destroys already formed granules. This is like kneading dough—moderate kneading makes the dough more elastic, but over-kneading damages the gluten structure.

IV. Lifter Design: The “Architect” Inside the Drum

Lifters are bars fixed to the drum’s inner wall; their shape and number directly influence particle motion trajectories. By comparing DEM simulation results for different lifter designs, researchers found:

· Straight Lifters: Simple but less efficient, prone to creating “dead zones” in front of the lifter where particles accumulate without participating in mixing.

· Curved Lifters: Can lift particles more smoothly, reducing energy loss, making particle cascading trajectories more uniform, and increasing particle sphericity by 10%-15%.

· Number of Lifters: More is not always better. Too many lifters reduce the lifting height of particles, actually decreasing mixing effectiveness; too few lifters provide insufficient lifting capacity. DEM simulation can help determine the optimal number and arrangement of lifters.

These findings directly guide equipment manufacturers in optimization design. Many modern drum granulators already employ lifter configurations optimized based on DEM simulation results.

V. From Virtual to Reality: The Practical Value of DEM

The value of DEM simulation lies not only in understanding mechanisms but also in guiding practice:

Reducing R&D Costs and Risks

Traditional granulation process optimization requires repeated physical experiments, each consuming a large amount of raw materials and energy, and adjusting equipment parameters is both time-consuming and labor-intensive. Discrete element method (DEM) simulation allows for rapid testing of dozens or even hundreds of parameter combinations on a computer, enabling the selection of the most promising ones for physical verification. This can shorten the development cycle by more than 60% and reduce costs by more than 50%.

Optimizing Performance of Existing Equipment

For granulation equipment already in use, the Discrete Element Method (DEM) can diagnose performance problems: Is the rotation speed inappropriate? Is the lifting blade design unreasonable? Or are there problems with the binder addition method? Through “digital twin” technology, a virtual model is created for each piece of equipment, allowing for the development of personalized optimization plans.

Accelerating New Product Development

When developing new types of fertilizers (like slow-release or functional fertilizers), DEM can predict the granulation behavior of new materials in existing equipment, identifying potential problems in advance and reducing trial-and-error attempts.

VI. Future Outlook: More Realistic, Smarter Simulations

Although DEM has achieved significant success, there is still room for improvement. Current models mostly assume particles are perfect spheres, while actual material particles are often irregularly shaped. Future DEM will integrate more complex non-spherical particle models. More importantly, researchers are developing “CFD-DEM coupling methods,” combining Discrete Element Method with Computational Fluid Dynamics to simultaneously simulate particle motion and fluid flow (binder liquid, air), achieving true multiphase flow simulation.

With increasing computational power and improved algorithms, future DEM simulations will become more accurate and efficient. Perhaps soon, before designing a new production line, fertilizer manufacturers will conduct comprehensive digital simulations to ensure successful commissioning on the first attempt. The Discrete Element Method is bringing the ancient craft of granulation into a new era of digitalization and intelligence.

The Digital Revolution in Fertilizer Granulation Technology

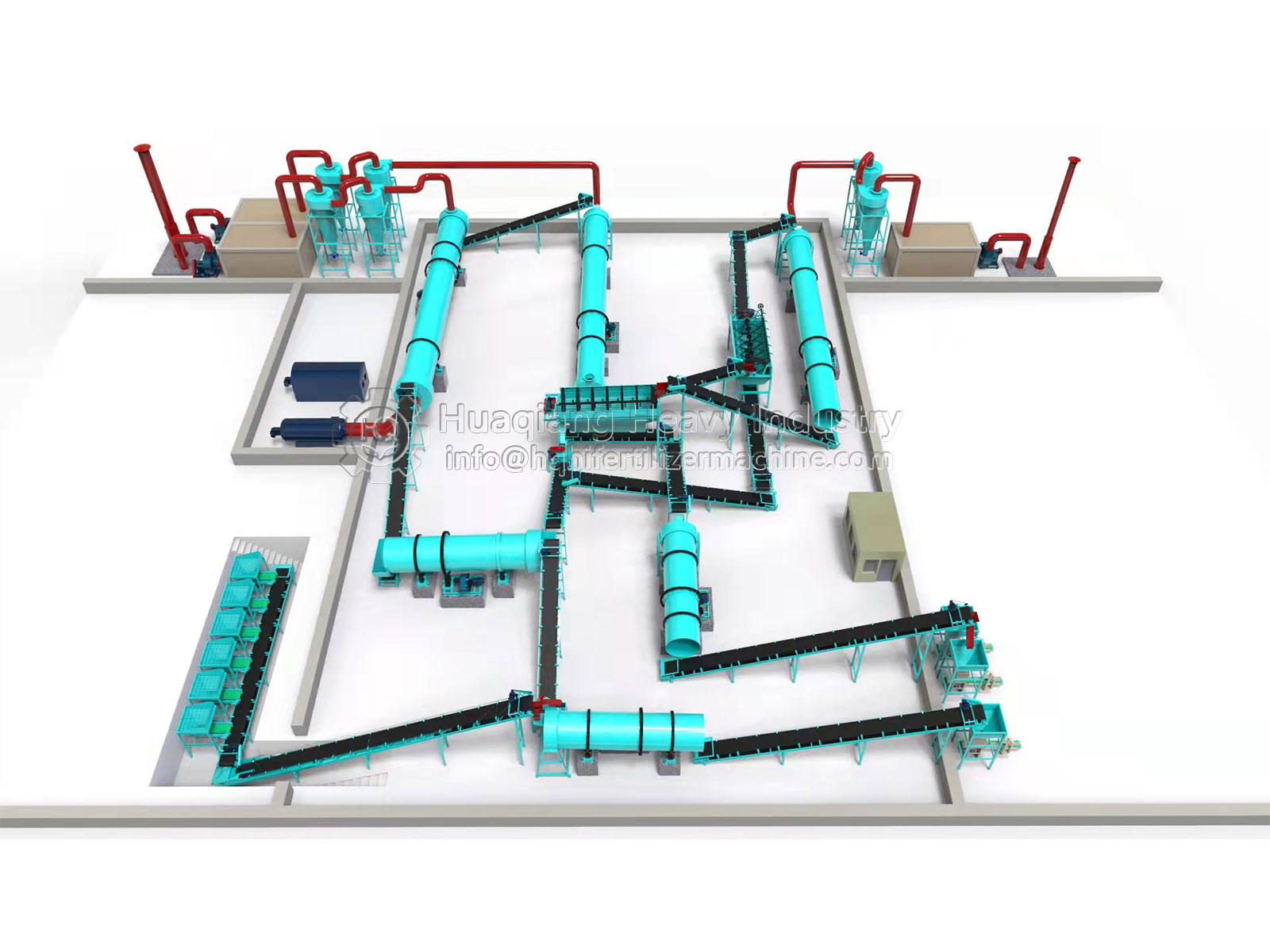

The Discrete Element Method acts as a “digital microscope,” transforming our understanding and optimization of fertilizer granules compaction and other npk fertilizer production technology. This advanced simulation allows engineers to probe the complex dynamics inside a rotary drum granulator or a fertilizer compaction machine, moving from empirical trial-and-error to predictive science. By modeling particle interactions in a virtual environment, it enables the precise design and refinement of equipment, such as optimizing the pressure distribution in a roller press granulator production line or the flow patterns in a disc granulation production line.

This computational power is revolutionizing the entire npk manufacturing process. It allows for the virtual testing of different raw material properties and machine parameters before physical prototypes are built, accelerating innovation in fertilizer production machine development. The shift towards such digital, predictive engineering is a powerful driver for creating more efficient, energy-saving, and intelligent granulation systems, ultimately supporting the goals of sustainable agriculture and precision manufacturing through smarter, science-driven production.