Chlorine is an essential micronutrient for plant growth. Although often overlooked, the chlorine element in fertilizers processed by fertilizer granulators can contribute to plant health by regulating physiological metabolism. The key lies in precisely matching crop needs and application rates.

Chlorine’s beneficial effects on plant health are clear. Firstly, it participates in photosynthesis, assisting in chlorophyll synthesis and photosynthetic product transport, thereby improving photosynthetic efficiency. Secondly, it regulates cell osmotic pressure, balances water content, and enhances the plant’s resistance to drought and salinity. Thirdly, it inhibits the growth of fungi and bacteria, promotes root development, and strengthens nutrient absorption.

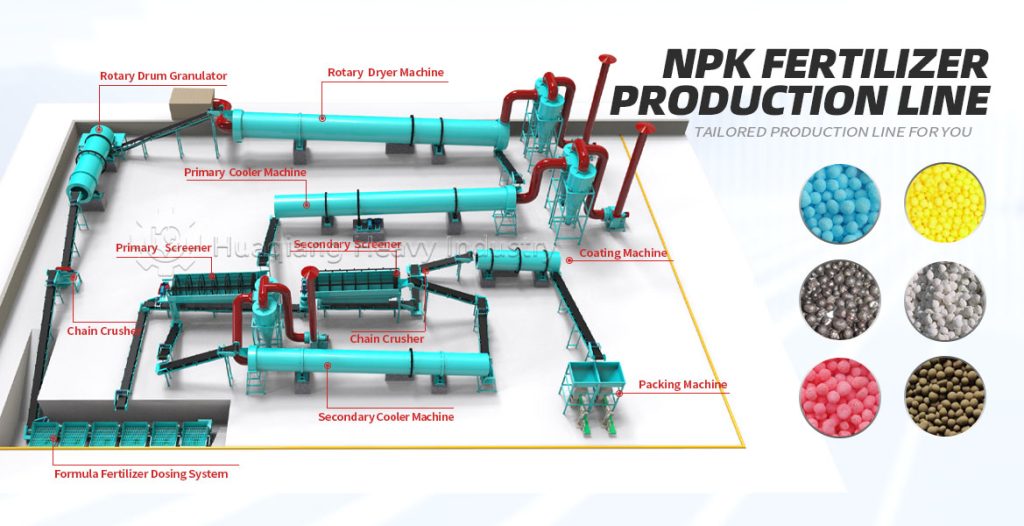

Crops vary greatly in their tolerance to chlorine, requiring precise application. Chlorine-loving crops such as corn and rice can benefit from appropriate application of chlorine-containing fertilizers processed by rotary drum granulators, leading to improved quality and increased yield. However, chlorine-sensitive crops such as tobacco and strawberries can suffer from excessive chlorine absorption, resulting in leaf scorching and reduced fruit quality; therefore, chlorine-containing fertilizers should be avoided.

Scientific application is crucial. It is necessary to control the amount of chlorine-containing fertilizers to avoid chlorine accumulation in the soil; combining them with organic fertilizers can mitigate the irritating effects of chlorine; chlorine-sensitive crops should use chlorine-free fertilizers, while chlorine-loving crops can use chlorine-containing fertilizers in combination with nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium fertilizers.

In summary, chlorine in chlorine-containing fertilizers is an “invisible helper” for plant health. By using standardized products processed by fertilizer granulators and applying them precisely according to crop characteristics, its value can be fully realized.