Introduction: The “Odor Challenge” in Vegetable Waste Treatment

As a major vegetable producer, China generates over 245 million tons of vegetable waste annually. Improper handling of discarded tomato stalks, cabbage leaves, and similar waste not only occupies space but also produces complex volatile organic compounds (VOCs) during composting, emitting unpleasant odors. A recent study on the co-composting of tomato stalks and cow manure systematically revealed, for the first time, the 58 different VOCs produced during this process and tracked the succession of microbial communities driving the fermentation. This research not only explains the source of compost odors but also provides scientific basis for optimizing composting processes and reducing environmental pollution.

I. The “Odor Map” in Composting: A Symphony of 58 Chemical Compounds

During the 40-day composting cycle, researchers detected a surprising 58 volatile organic compounds. These substances form a complex chemical symphony, including nine major categories: sulfur-containing compounds, alcohols, esters, aldehydes, ketones, halogenated hydrocarbons, aromatic hydrocarbons, alkanes, and alkenes.

Who are the main “culprits”?

Not all detected compounds produce noticeable odors. The study showed that seven substances exceeded the human olfactory threshold: methyl sulfide, ethanol, n-butanol, ethyl acetate, acetaldehyde, butyraldehyde, and α-pinene. Additionally, ammonia (NH₃) was a significant odor contributor.

Methyl Sulfide—This substance, smelling like rotten cabbage, is one of the most important sulfurous odor components in compost. The study found its concentration peaked around day 20 (0.1926 mg/m³). Interestingly, its production is closely related to the presence of anoxic zones within the compost pile. When turning frequency decreases, anaerobic microenvironments easily form inside the pile, promoting methyl sulfide generation.

Ammonia—Persists throughout the composting process as a byproduct of nitrogen transformation. Its production is directly related to the efficiency of nitrogen loss in composting.

Unexpected Discoveries

The study also detected a large number of aromatic hydrocarbons (18 types), likely related to the added cow manure. Aromatic compound precursors in cow manure are converted into these volatile substances by microbial action. Although various alkanes (17 types) were detected, their concentrations were low, contributing little to the overall odor.

II. The Dance of Temperature and the Breath of Oxygen

The composting process involves dynamic changes in temperature and oxygen. The study found:

Temperature Changes: By the 4th day of composting, the temperature exceeded 50°C. The high-temperature period (>55°C) lasted over 15 days, sufficient to kill pathogens and ensure compost sanitization. The temperature curve showed a typical rise-then-fall pattern, reflecting the intensity of microbial activity.

Oxygen Consumption: Oxygen concentration showed fluctuating changes. During days 20-25, when compost temperature remained high and microbial activity was vigorous, oxygen consumption peaked, and oxygen content within the pile reached its lowest. Increasing the turning frequency at this point (from once every 3 days to once every 2 days) effectively increased oxygen concentration and alleviated local anaerobic conditions.

III. The Invisible Workers: Microbial Community Succession

Composting is essentially a microbe-driven biotransformation process. High-throughput sequencing revealed the fascinating succession of bacterial and fungal communities:

The Bacterial Kingdom: Four Phyla Dominate

Firmicutes, Chloroflexi, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria were the dominant bacteria during composting, constituting over 80% of the total bacterial community.

In the initial composting stage (1-15 days), the abundance of Firmicutes increased; this phylum includes many species capable of decomposing cellulose and hemicellulose. The abundance of Chloroflexi gradually increased in the early stage, peaking around day 25 before declining. At the genus level, the abundance of Bacillus increased continuously from start to finish, directly related to its cellulose-degrading ability.

The Fungal World: Three Major Groups Take Turns

Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Mucoromycota were the dominant fungal groups.

Ascomycota dominated throughout the composting process; these fungi are widespread and can degrade lignocellulose. During days 1-10 of composting, as temperature rose, thermophilic fungi like Thermomyces rapidly multiplied and became dominant. From days 10-20, Thermomyces was replaced by Mycothermus, which may play a key role in decomposing remaining macromolecular substances.

Microbial Association with Odor

The study also identified microorganisms significantly associated with ammonia production. Among bacteria, genera like Desulfitibacter, Paenibacillus, and Haloplasma were related to ammonia concentration; among fungi, genera like Meyerozyma, Alternaria, Hapsidospora, and Aspergillus were closely associated with ammonia production. These findings provide potential targets for controlling compost odor by regulating microbial communities.

IV. Principal Coordinates Analysis: Visualizing Community Changes

Using Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA), researchers visually demonstrated microbial community changes:

Bacterial communities were relatively stable in the first 25 days, with sample points clustered closely; after 25 days, community structure changed noticeably with oxygen concentration variations.

Fungal communities underwent three distinct succession stages: the low-temperature period of the first 5 days, the high-temperature period after heating, and the mature stabilization period after 20 days. The fungal community structure differed significantly in each stage.

V. Practical Implications: How to Reduce Compost Odor?

Based on this research, we can derive practical suggestions for reducing odor in vegetable composting:

- Optimize Turning Strategy:During the high-temperature, high-oxygen-consumption period around days 20-25, appropriately increase turning frequency to reduce the formation of anaerobic microenvironments, thereby lowering the production of malodorous substances like methyl sulfide.

- Adjust Feedstock Ratio:Pay attention to the proportion of cow manure added to avoid excessive aromatic compound precursors entering the composting system.

- Inoculate Functional Microorganisms:Consider inoculating microbial agents that efficiently degrade sulfur-containing compounds or fix ammonium nitrogen.

- Process Monitoring:Use methyl sulfide and ammonia concentrations as indicators for composting process monitoring, adjusting process parameters promptly.

From Odor Management to Efficient Fertilizer Production

The scientific insights into odor formation during organic fertilizer fermentation directly inform the optimization of industrial-scale organic fertilizer manufacturing. Understanding microbial succession and volatile compound production allows for the refinement of fermentation composting technology for organic fertilizer. Key to this is implementing precise fermentation composting turning technology to manage aeration and temperature, thereby minimizing malodorous emissions and enhancing the efficiency of the decomposition process within a complete organic fertilizer production line.

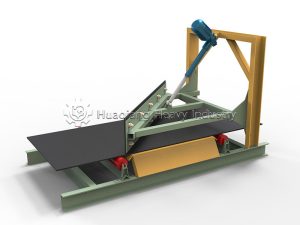

Following this optimized, scientifically managed fermentation, the stabilized compost proceeds to the final processing stage. Here, an organic fertilizer granulator—such as an innovative new type two in one organic fertilizer granulator that combines mixing and shaping—transforms the material into uniform pellets. This granulation step is a core component of both standard and bio organic fertilizer production line configurations. The entire workflow demonstrates how fundamental research on composting biochemistry is applied to engineer efficient, environmentally sound systems that convert challenging organic waste into valuable, market-ready soil amendments.

Conclusion

Co-composting of vegetable waste and cow manure is a complex biochemical process accompanied by the production of diverse volatile organic compounds and dynamic microbial community succession. Understanding the chemical nature of these odors and their relationship with microbial activity is key to developing efficient, low-odor composting technologies. This study not only provides theoretical guidance for the resource recovery of vegetable waste but also contributes important scientific basis for the green transformation of the composting industry and sustainable agricultural development. In the future, based on these findings, we can design smarter composting systems that minimize environmental impact while transforming organic waste, truly realizing the circular agriculture dream of “turning waste into treasure.”