Organic fertilizer, a cornerstone of sustainable agriculture, derives its effectiveness from three core “ingredients,” a concept defined by two complementary perspectives: the essential nutrients it provides for plant growth and the primary raw materials that form its composition. These ingredients work in synergy to nourish plants and improve soil health, and their transformation into high-quality fertilizer is largely dependent on fermentation—a vital microbial process that breaks down raw materials into stable, nutrient-dense forms. Understanding both the key ingredients and the role of fermentation is essential to grasping the value and production logic of organic fertilizer in 2026.

From the perspective of essential nutrients, the three main ingredients of organic fertilizer align with the universal NPK framework that categorizes all fertilizers. Nitrogen (N), the first core nutrient, is critical for promoting lush, green foliage growth as a key component of chlorophyll, which drives photosynthesis. Phosphorus (P) focuses on underground and reproductive growth, stimulating robust root development and encouraging the production of flowers, fruits, and seeds—directly enhancing crop yield and quality. Potassium (K), the third essential nutrient, acts as a “health booster,” strengthening plants’ disease resistance and their ability to withstand environmental stresses such as cold, drought, or salinity. Unlike synthetic fertilizers that deliver these nutrients in concentrated chemical forms, organic fertilizer provides NPK through natural, slow-release compounds that nourish both plants and soil microbes.

From a manufacturing standpoint, the three primary raw material classes constitute the physical “ingredients” of high-quality organic fertilizer in 2026. The first class is animal by-products, which are rich in nitrogen and phosphorus. Common examples include cattle and poultry manure, bone meal, and blood meal—materials that are nutrient-dense but require thorough treatment to eliminate pathogens and odors. The second class is plant-based materials, which offer a balanced nutrient profile and play a key role in improving soil structure. Compost, alfalfa meal, cottonseed meal, and seaweed/kelp meal fall into this category, providing not only NPK but also organic matter that enhances soil aeration and water-holding capacity. The third class is carbon sources, essential for feeding beneficial soil microbes and regulating nutrient release rates. In 2026, common carbon sources include straw, biochar, and sawdust—materials that extend the fertilizer’s effectiveness by supporting microbial activity in the soil.

A critical link between these raw materials and usable nutrients is fermentation, a microbial process that transforms bulky, potentially harmful organic wastes into stable, plant-friendly fertilizer. Fermentation in organic fertilizer production primarily relies on four main biochemical pathways, each contributing to the decomposition and nutrient transformation of the three core raw material classes. Alcoholic fermentation, driven by yeasts like Saccharomyces cerevisiae, initiates the breakdown of carbohydrate-rich plant materials (such as straw and grain residues) by converting sugars into ethanol and carbon dioxide, serving as a transitional stage for further decomposition. Acetic acid fermentation, an aerobic process carried out by Acetobacter bacteria, oxidizes ethanol into acetic acid, which helps break down complex organic matter like lignin in plant residues and adjusts the fermentation environment’s pH to suppress pathogenic bacteria—critical for processing plant-based materials safely.

Butyric acid or alkali fermentation plays a key role in processing animal by-products. Clostridium bacteria and proteolytic microbes drive this anaerobic process, breaking down proteins and fats in manure, bone meal, and blood meal into amino acids, ammonia, and other alkaline compounds. This not only eliminates odors and pathogens but also converts unstable nitrogen and phosphorus into forms that plants can absorb gradually. Lactic acid fermentation, though less direct, contributes by adding probiotic lactic acid bacteria that improve the microbial balance of the fermentation matrix, indirectly enhancing nutrient conversion efficiency.

In 2026, industrial organic fertilizer production primarily adopts solid-state fermentation (SSF), a cost-effective process where microbes grow on moist solid substrates (the three raw material classes) with little to no free water. This method efficiently converts bulky raw materials into granular or powdered fertilizer, realizing resource recycling. For gardeners and small-scale farmers, specific raw materials can be selected to target nutrient needs: blood meal, feather meal, and composted poultry manure are top sources for boosting nitrogen; bone meal and rock phosphate excel at increasing phosphorus; and kelp meal, wood ash, and naturally mined sulfate of potash are ideal for enhancing potassium levels—all of which require appropriate fermentation to unlock their full potential.

In summary, the three main ingredients of organic fertilizer are dual-faceted: NPK as the essential nutrient core and animal by-products, plant-based materials, and carbon sources as the primary raw material foundation. Fermentation acts as a bridge between these raw materials and usable nutrients, leveraging microbial activity to decompose, purify, and transform ingredients into stable, effective fertilizer. As sustainable agriculture advances in 2026, the rational matching of these three core ingredients and the optimization of fermentation processes remain key to maximizing the value of organic fertilizer, fostering healthy soil ecosystems, and ensuring long-term agricultural productivity.

Mechanized Production Systems for Commercial Organic Fertilizer

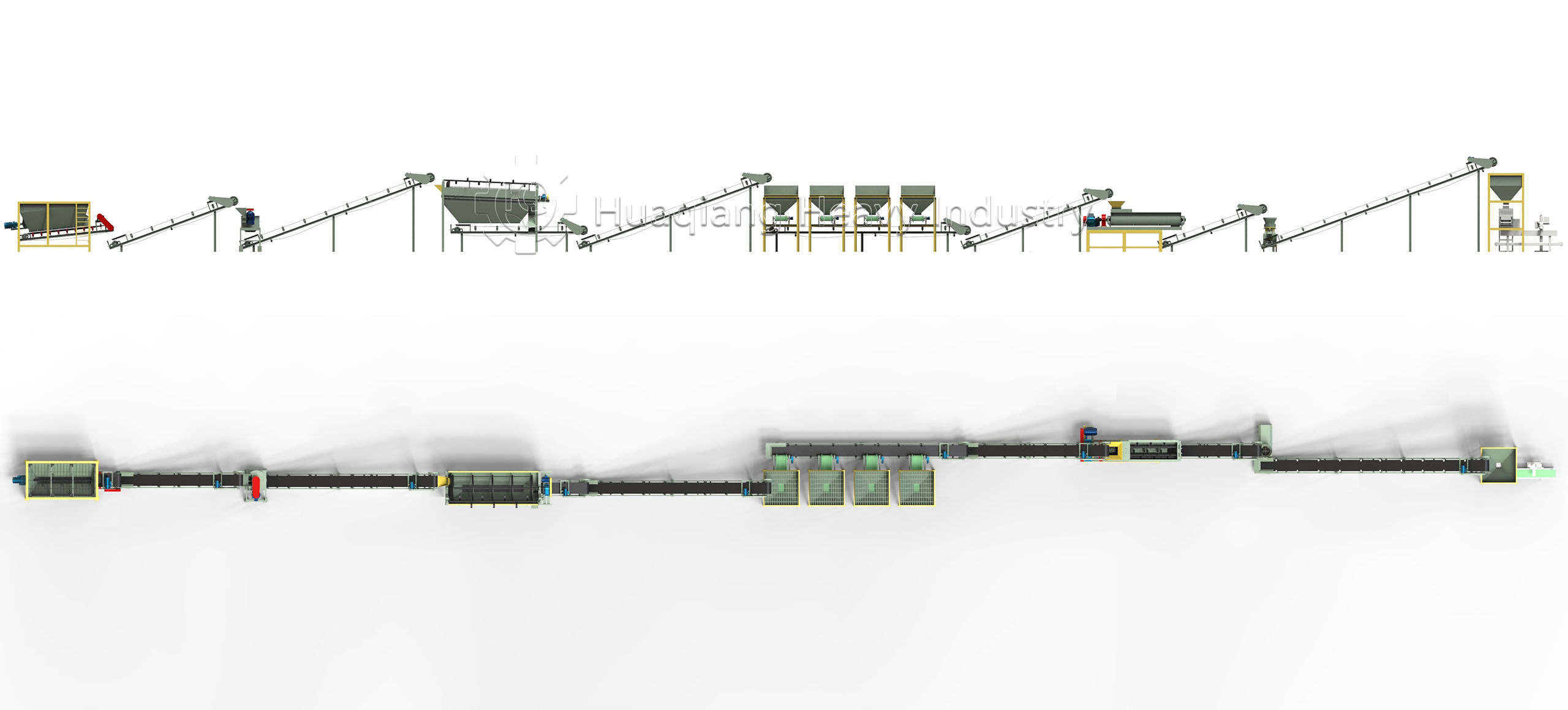

The transition from fermented raw materials to a commercial product requires a dedicated organic fertilizer manufacturing system. A standard organic fertilizer production line integrates several stages. Following fermentation, which is often accelerated by equipment like a large wheel compost turning machine or a chain compost turning machine for aeration, the cured material is ready for shaping. The core process of organic fertilizer production granulation offers multiple technological paths. A traditional and effective method is the organic fertilizer disc granulation production line, which forms spherical pellets through a tumbling action.

For different product specifications, alternative granulation equipment is available. A flat die press pellet machine for sale produces dense cylindrical pellets via extrusion. For operations seeking process integration and space savings, a new type two in one organic fertilizer granulator combines mixing and granulation in a single unit. More complex organic fertilizer combined granulation production line setups may sequentially employ different granulators to achieve optimal particle structure. When incorporating specific microbial consortia post-fermentation, the system evolves into a specialized bio organic fertilizer production line, where gentle granulation is crucial to preserve microbe viability.

This mechanized organic fertilizer manufacturing approach ensures the efficient transformation of locally sourced, fermented organic ingredients into standardized, easy-to-apply fertilizers, closing the loop in sustainable nutrient management and adding significant value to agricultural by-products.